The form is the fundamental question at issue in any endeavour to create a work of art. It is about the style one chooses to build a world, with aspirations for a structure which will reverse their skepticism so as to nurture the values that reorganize chaos in sacred order. In other words inhabit a world made of the same material as the big world – violence, joy, war, love, lust, death, despair – including conscience and a potential reconciliation with mother uncertainty, as would Heisenberg say, loosely translated. This does not mean that the form is a conception in the mind waiting to be fulfilled, since the artists are in constant awareness of life events and activities around them, so while life is self-organizing they are pondering over in order to resume vigorously and more intensely their objective: the accomplishment of their work. Their obsessions, their faith in their commitment are few of their weapons and the driving force from which they draw their confidence. As you see, the vital issue of the form remains a vexed question raised by many artists, occasionally taken to an extreme. Among them the painter Kazimir Malevich who drew the black square in 1915 at the peak of World War I, though the inspiration of this painting came earlier, in 1913. Originally ‘the Square’ lacked any symbolism, its objective was purely artistic. However, there were many interpretations and even more controversies. According to Malevich himself he created the painting in a state of mystic ecstasy. If you take a closer look, the paint in the square weathered by age thus creating the illusion of a figure, which allows even more commentary on a painting which has been commented on as few have in the history of art. Much can be said and even more one can think of about it, no matter how we perceive it, though, it still is one of the works of art that have had the greatest influence on the evolution of art in the 20th century. The black square is the scope of the invisible for every viewer who faces it. It almost forces them to challenge their inner darkness. When it was first exhibited in 1925, it was placed without any information, at the demand of the artist himself, high up in one corner of the hall where the two walls are joined (known as the red corner where people placed anything valuable in their homes at the time) to indicate the icon corner, and give a sense of a sacred icon. The black square could represent the rectangular void of inhibited action.

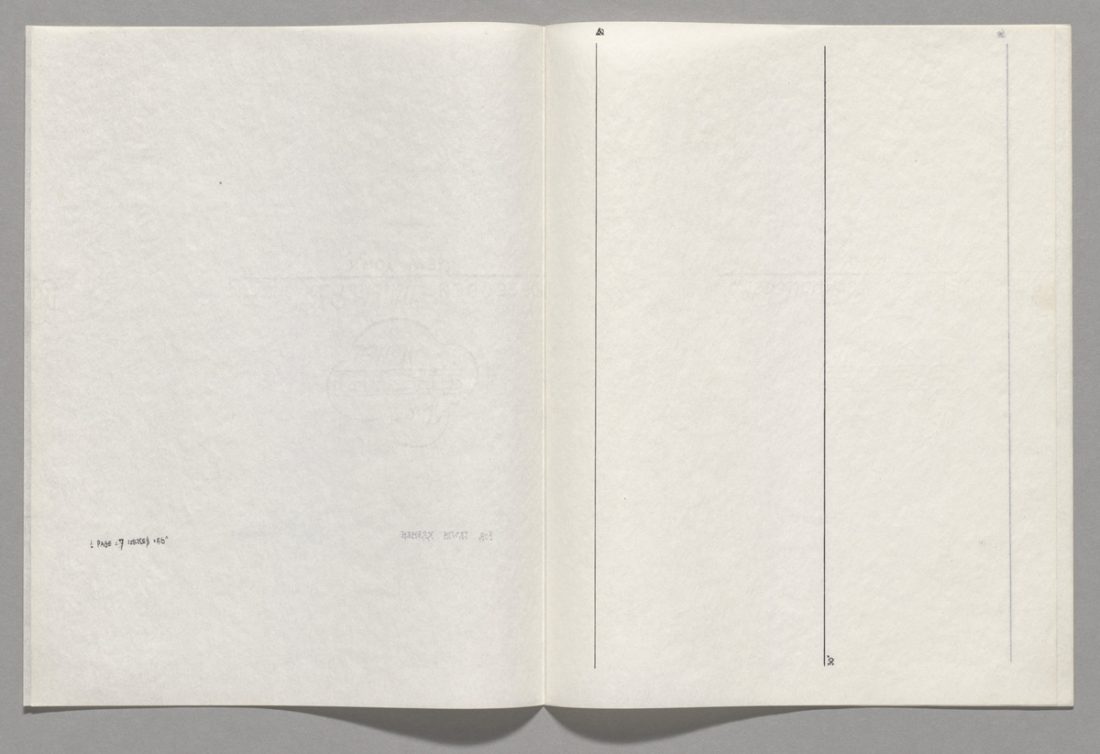

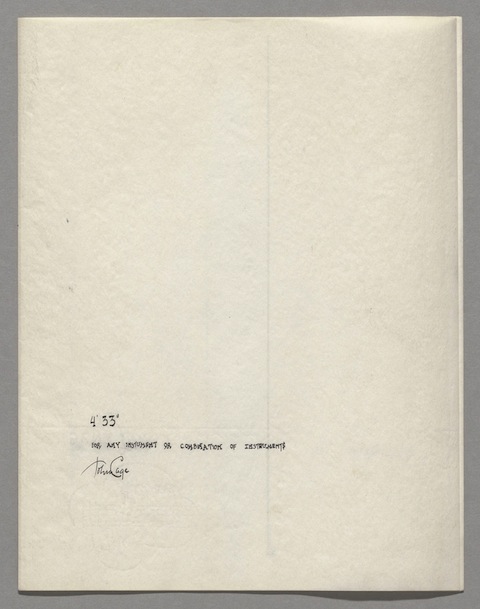

In his appearance in1952 the musician John Cage played on his piano the piece ‘there is no such thing as silence’. The music score for this piece consists of vertical hand drawn black lines instead of notes, which suggest time units, denoted by the respective spaces on the paper. On the fourth line we can see written 1 page=7 inches=56 seconds. Much to their amazement the audience did not hear a single note, just silence which lasted for 4’33’’. Quoting John Cage ‘whatever we do is music’. The issue for Cage was not silence but the awareness of the ambient sound. As you may understand his extreme style provoked not only a multitude of discussions and heated debate concerning the art of music, but also beneficial questions. Could a mainstream musical work express Cage’s intentions? According to Cage the sound does not evaluate, interpret or explain, it does not ‘‘speak’’ it just ‘‘is’’. He cites Kant in “there are two things that don’t have to mean anything, one is music’’, in the same way as random noises do not mean anything. Cage was also a music theorist, a philosopher, a poet, a graphic artist and visual artist. In the long run the form might be the key solution for both aesthetics and spiritual issues.