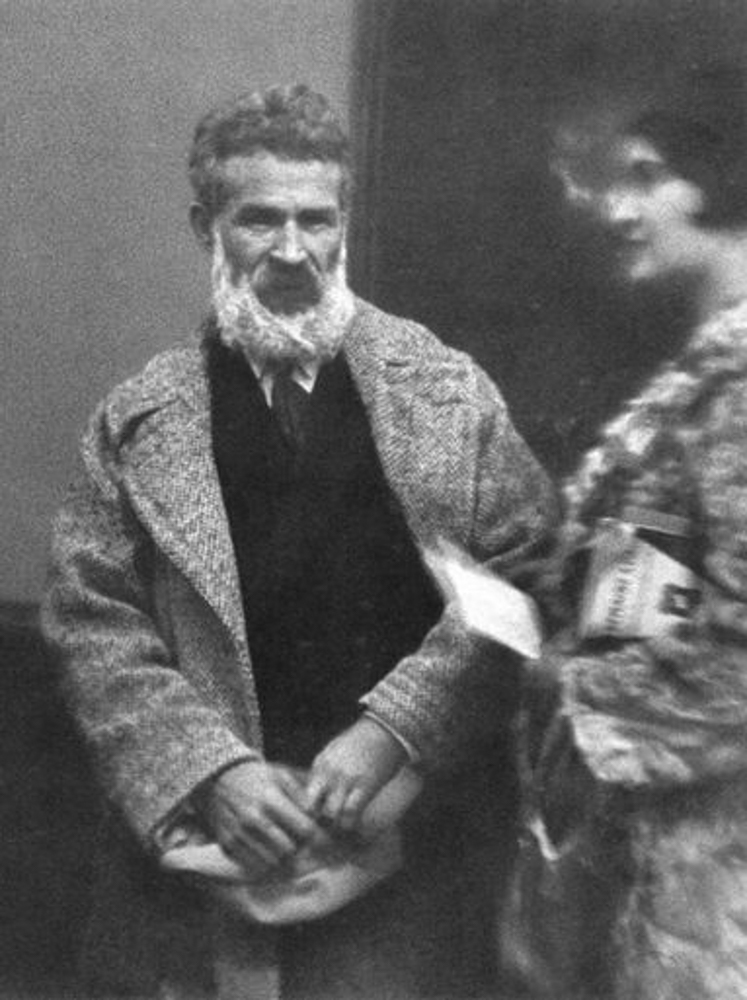

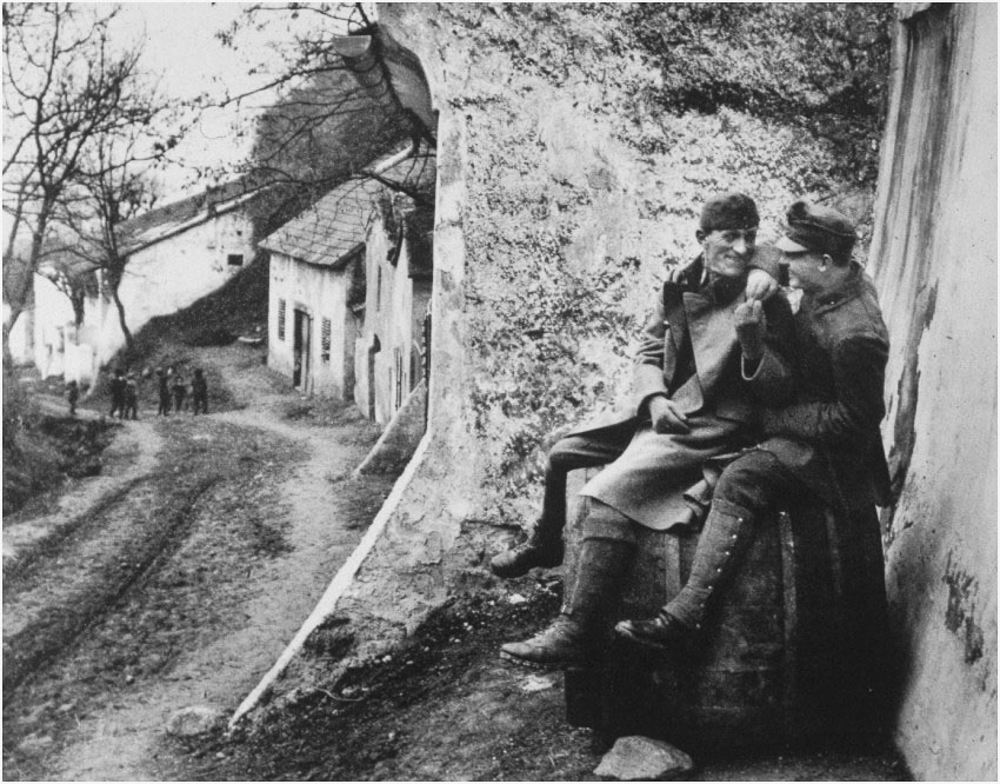

This picture was taken by André Kertész in 1915 in Esztergom, Hungary. It depicts two soldiers on Easter day cracking their eggs during World War I. He is 21 years old and serves his military service. Though this picture may not be one of his best, it showcases a quality of the photographer more aptly than many other of his eventually more important images. That is his quality to approach his subject and the photographic process. In contrast to the plethora of known photos taken in wartime, Kertész’s images are focused on the lives of soldiers away from the battlefield. Kertész’s genius was partly based on his ability to turn our attention to apparently “insignificant” images. His sensitivity creates imprints of joy but also of contemplation beyond the trenches. He revolutionized the use of the recently invented handheld camera of that time.

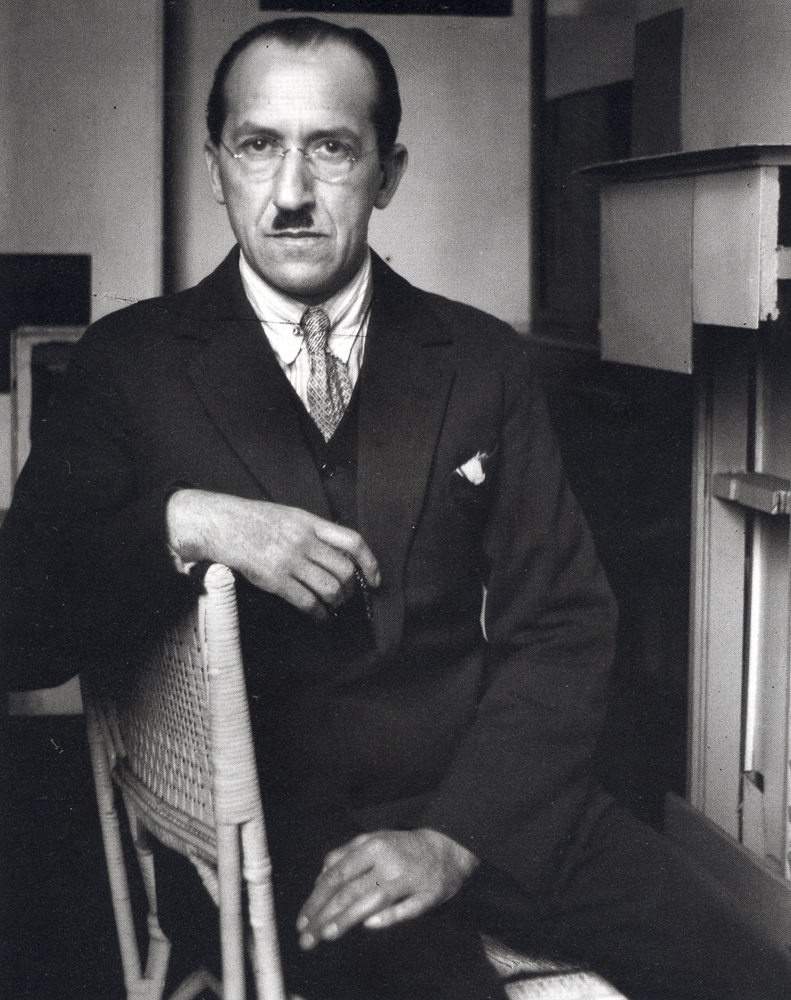

In 1925 Kertész made the crucial decision to move to Paris. There, he got acquainted with and became a member of a big circle. His portraits of Piet Mondrian, Marc Chagall, Alexander Calder, Constantin Brancusi, Sergei Eisenstein, Tristan Tzara are among those making up the great collection of his photographs. This group of people set fire to each one of the remnants of the sterile Academism of the time. By 1927, his photographs on the streets of Paris began to arouse genuine interest. It was an era of emergence of a new perception of the world. As a result, an exhibition of 42 photographs was held in an avant-garde gallery of the time.

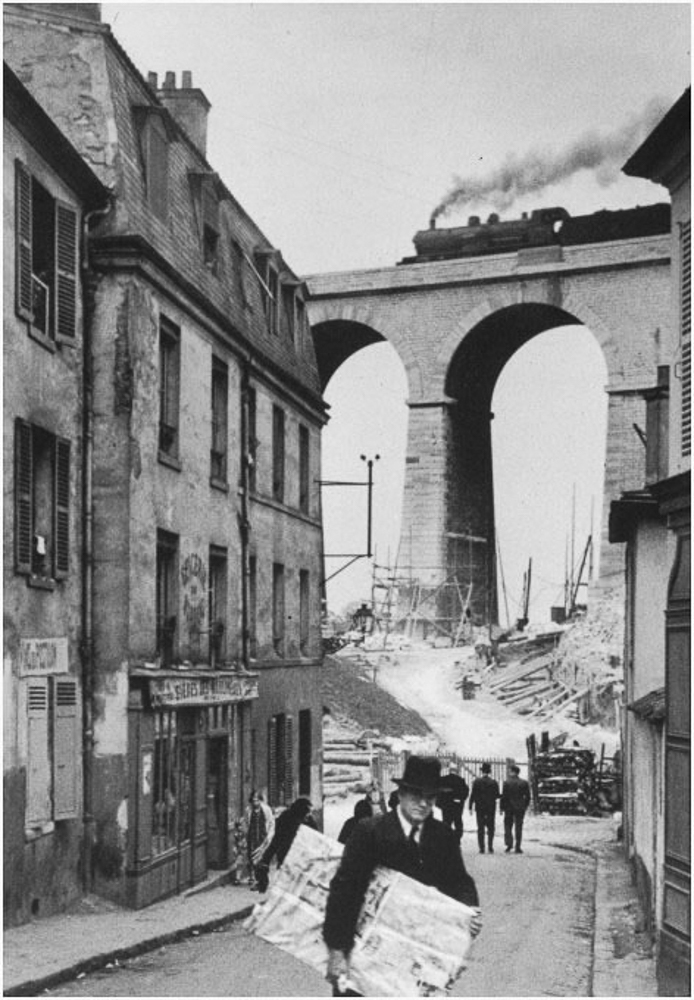

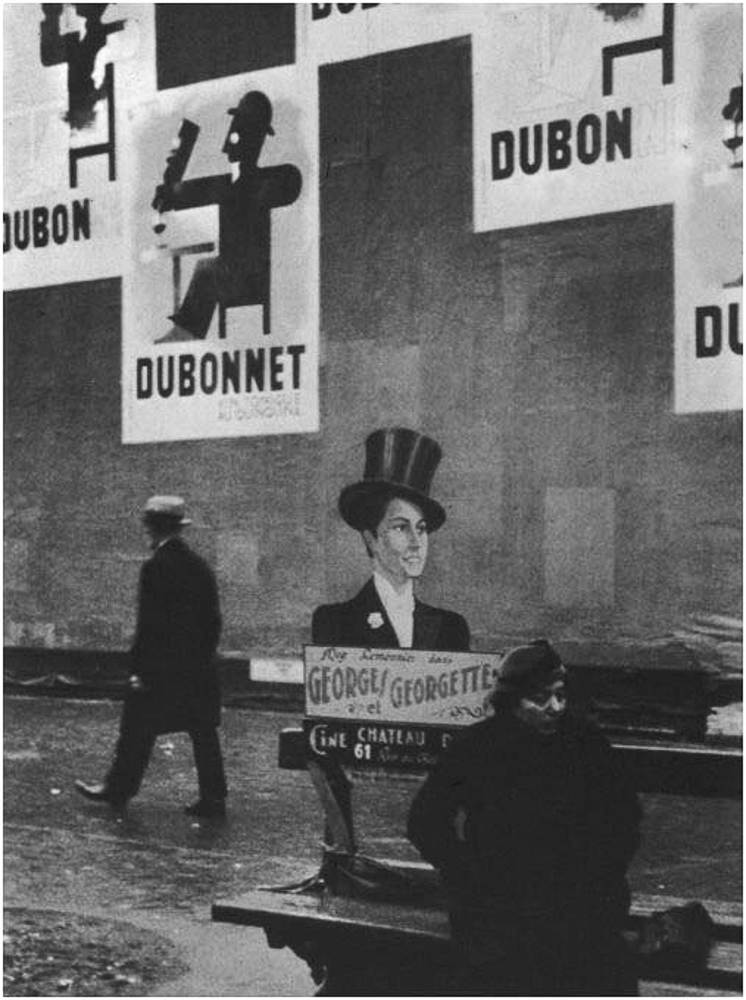

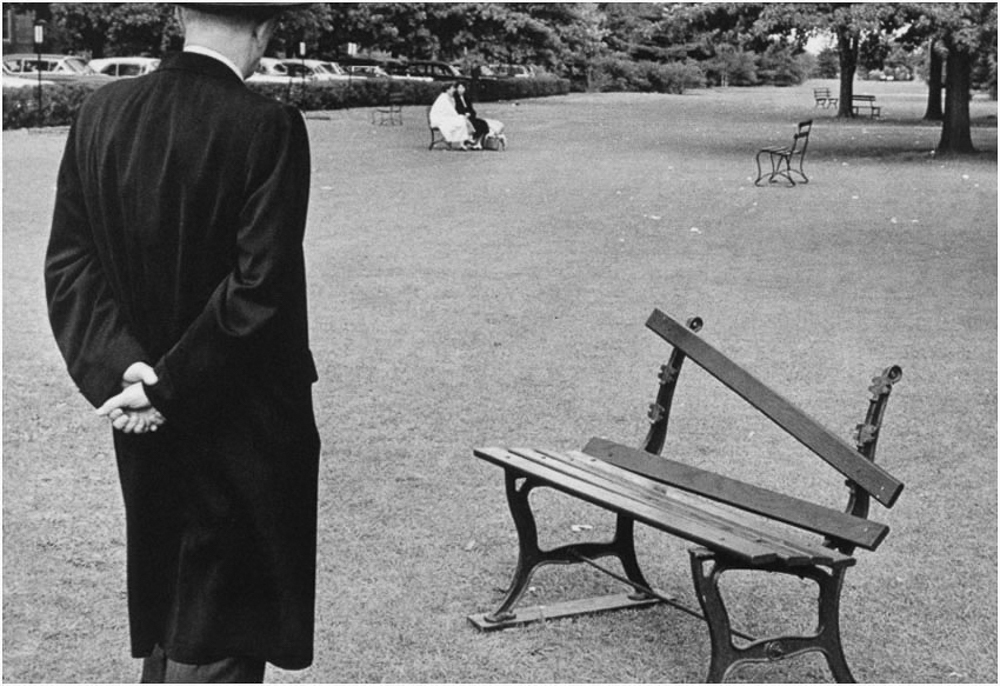

The world as a scenery is an inexhaustible source of images surpassing the imagination of any inventive photographer. André Kertész was well aware of this and knew also how to transform every aspect of life into photographic events. Quite often, in street photography, but not only, photographers’ clicks are swallowed up by the demon of journalism. Photographic imaging is restricted to the depiction of events without transformation or metaphorical dimension. A simple description, or something equivalent and more complete, could give meaning to the values of daily life. The surrealism and the elements’ unconventional relation that make up the image in Meudon in 1928, the broken photographic plate in 1929, the Dubo, Dubon, Dubonnet in 1934, as well as many other elements, exclude the absolute certainty in the images’ reading. All this makes ambiguity a dominant factor and has a beneficial effect on the viewer.

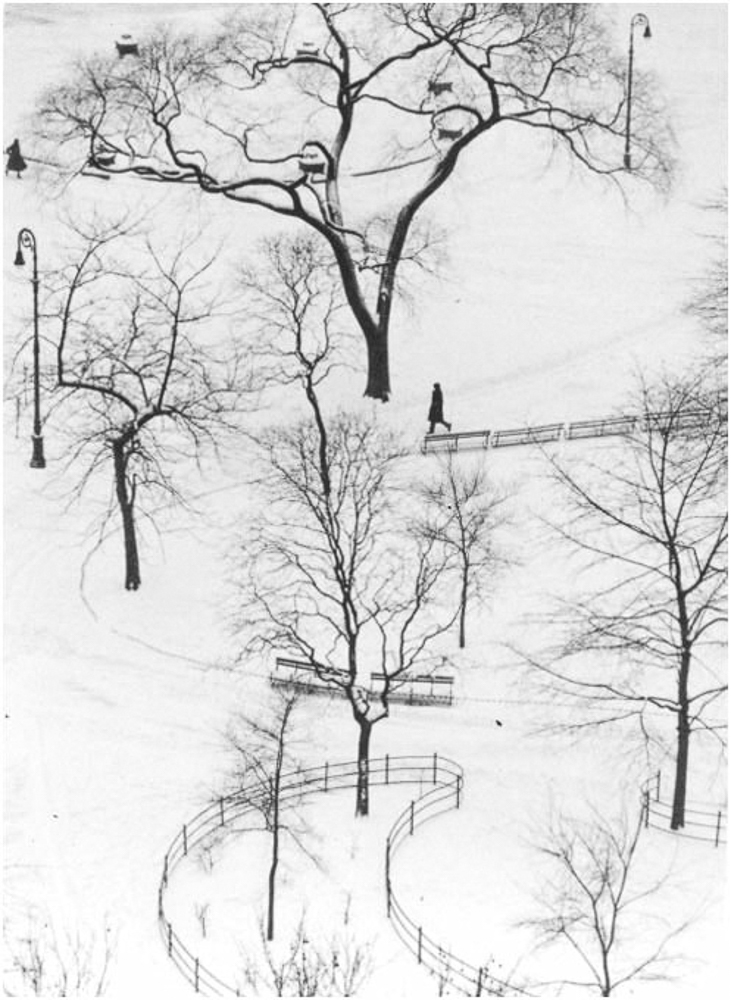

In 1936, after the death of his mother and his marriage to Elizabeth Saly, he moved to New York, where he signed a contract with the Keyston Agency. Though he canceled the contract a year later, the events and the imminent start of World War II made his return to Paris impossible. Unable to leave, and at the same time faced with hostility from the government (which prevented him from publishing for several years), Kertész found himself trapped in tragic irreconcilable circumstances. By the end of the war, he was deprived of the support of the artistic community, but continued to live in the United States due to health problems and family difficulties.

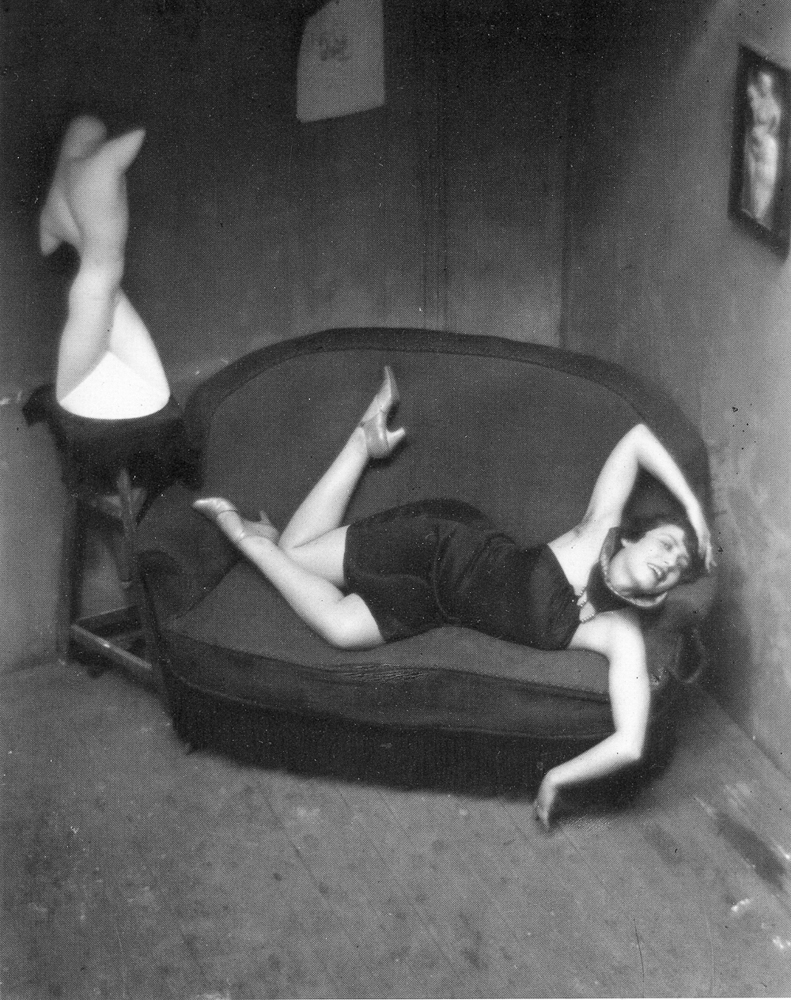

Nevertheless, the sweetness in Kertész’s gaze was preserved. His gaze embraces the whole world, even its harshest face, highlighting this precious, vulnerable and fragile part of the human potential, which is dragged down to its furious and obsessive propensity for power. His free-looking, without standards and preconceptions gaze explores, in a playful way, a complex and mysterious world in a seemingly simple and unintentional way, I dare say. The enjoyment of beauty, the authenticity of pure gaze leads to visual poetry in an unpretentious way,

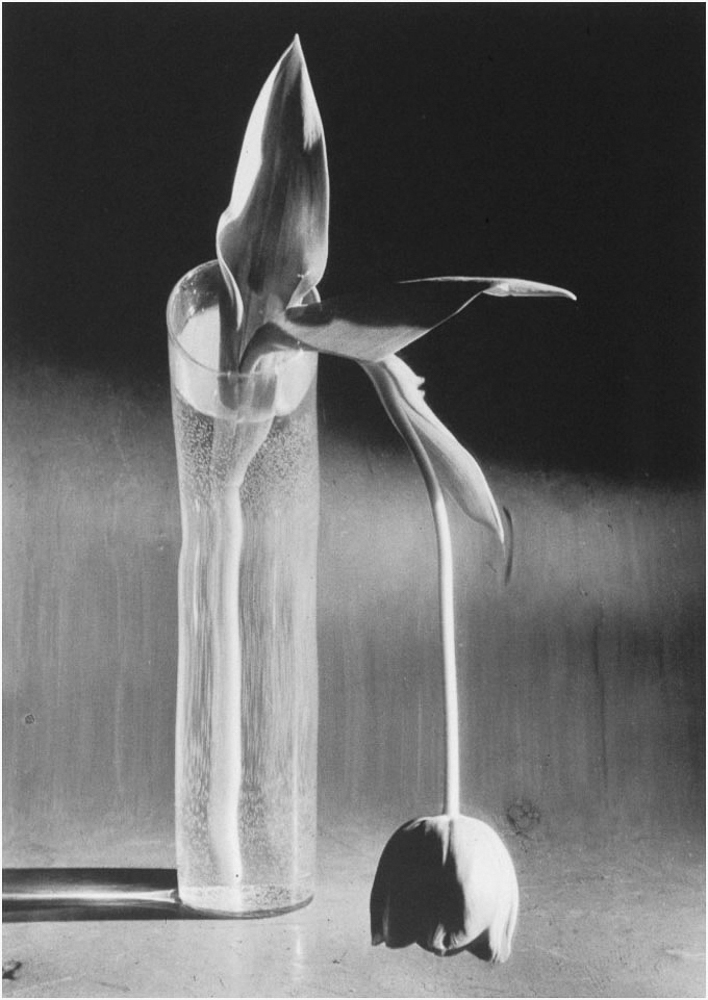

For almost twenty years his photographs remained unknown in New York. Only in 1964, when John Sarkowski, curator of the Museum of Modern Art, organized an exhibition, Kertész’s photographic life revived. As a result, the curvature of a hallucinogenic tulip, the melancholy of the open horizons of Martinique, the clump of blind umbrellas in Tokyo become public goods and travel worldwide. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Kertész appeared regularly in major international museums – with solo exhibitions in Paris, Tokyo, London, Stockholm, Budapest and Helsinki. In 1983, two years before his death, the French government awarded him the Order of the Knight of the Legion of Honor.

I am a photographer who entered the realm of photography by a side door. Being completely devoted to music, I believed that photography certifies or embellishes reality. I was not interested in either of these two functions, until a morning several years ago when an American friend showed me one of Kertész’s books while having coffee. André Kertész is my reason for being part of the world of photography. I realized, later, that there are two types of photographers. Those, whose images spring out and are often liked for the wrong reasons, and the others, the introverted, hermetically closed in their own world, who force us to invent the way to enjoy their art. Kertész belongs to the first category, but, I assure you, it is just as difficult to find the keys to entry.

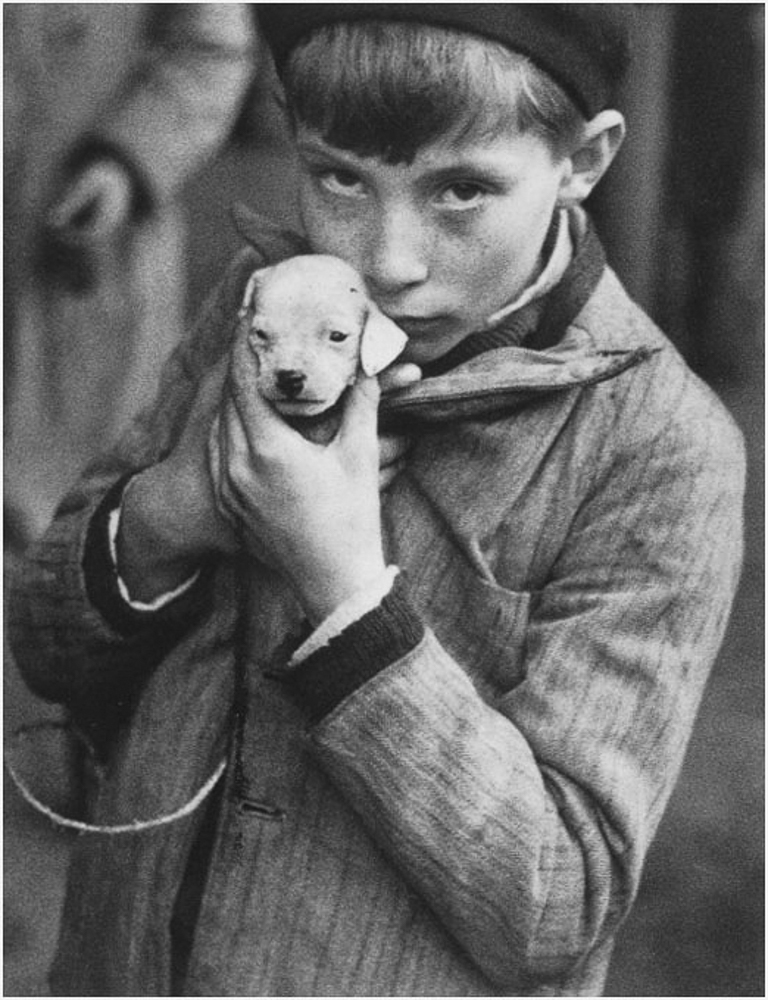

Roland Barthes, talking about the photo with the little boy – this poor kid who holds a newborn puppy in his arms and rest his cheek on it (1928) – and thinking about his gaze, which, without looking at something, seems to be introvert, writes “He looks into the lens, with his sad eyes, full of jealousy and fear, as if he was saying: What a pathetic heartbreaking reality! In fact, he doesn’t look at anything. He holds back his love and his fear. That’s the Gaze.“

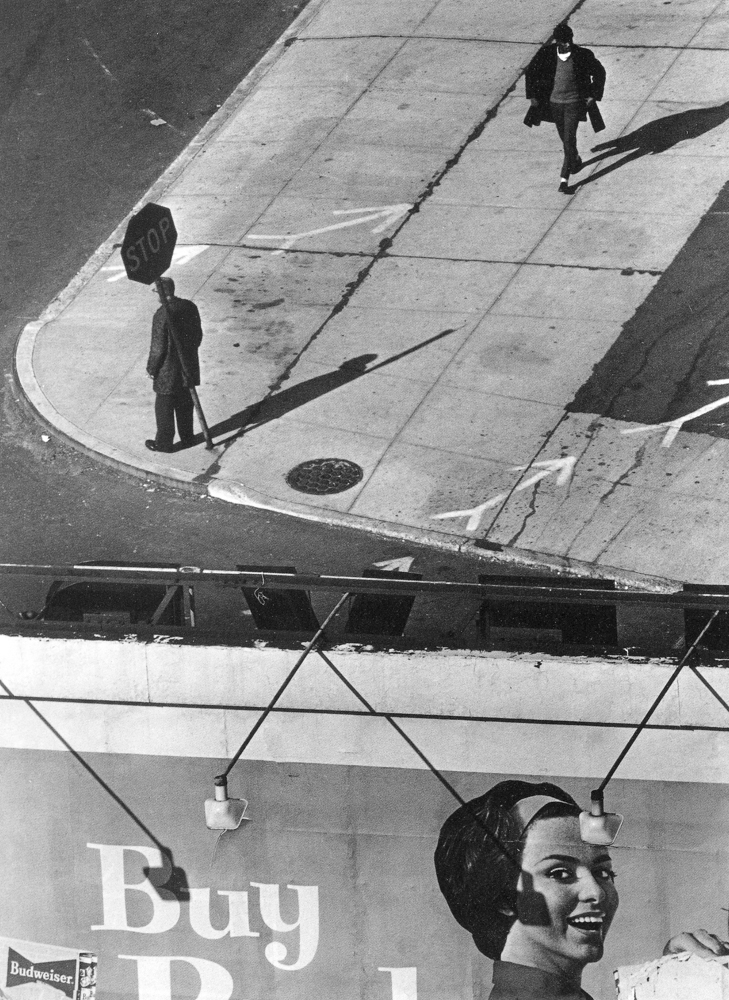

John Szarkowski, on the other hand, used to say that “Kertész loved the game. The surface of his photographs looks like an elastic and stretched visual bedspring” … I would add, in my turn, that is exactly how elastic and delicate the balance of our world is.